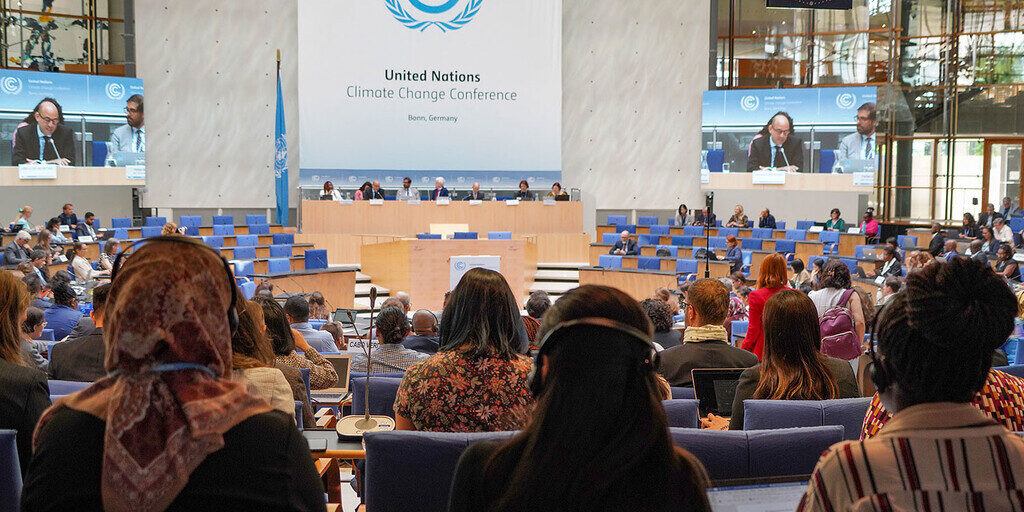

In June, a UN climate working session took place in Bonn. This is where the Subsidiary Bodies (SB) meet to decide which topics will make it onto the agenda of COP30 — the main climate conference of the year, set to take place in Brazil.

If a topic isn’t raised in Bonn, there’s a high chance it won’t become part of the official negotiations at COP. And it is at COP where political decisions are made — on how climate finance will be distributed, which countries will receive support, and who will bear the primary responsibility for emissions reductions.

For Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia, participating in the Bonn sessions is a chance to make their voices heard. Our region is often left out of the global climate spotlight. For instance, according to the Technical Assessment of the NBF Project for Central Asia and South Caucasus (UNFCCC, 2023), the region’s annual need for climate finance is estimated at USD 33 billion — yet it currently receives only around USD 1.7 billion, or just 5% of the required amount.

The Bonn talks are attended not only by official delegations, but also by activists, experts, and journalists — including participants from our region and members of the CAN EECCA network. They followed the negotiations, took part in meetings, and advocated for the priorities of their communities.

We’ve gathered their insights — so you can understand what was discussed in Bonn and why it matters for the EECCA region.

Iryna Ponedelnik, representative of the Green Network

Iryna Ponedelnik, representative of the Green Network

For me, the most important — and unfortunately, the most memorable — thing was that our region was once again overlooked, both by NGOs and civil society, and within the negotiations themselves.

Of course, our own efforts play a role here, but it felt as if, after COP29, everyone simply closed their eyes again. Some initiatives were presented — for example, on protecting mountain areas from Kyrgyzstan, or the upcoming Regional Environmental Summit set to take place in Kazakhstan in 2026. That’s encouraging: at least Central Asian governments are using this platform to advance regional climate policy. Unfortunately, we also witnessed a troubling moment: during discussions on the impact of wars on climate change, Palestine and Iran were mentioned repeatedly — but Ukraine was never brought up. Once again, our region was pushed into the shadows.

I presented a poster in the ACE (Action for Climate Empowerment) track, sharing results from last year’s EaP Youth Climate Leadership School. The ACE track focuses on climate education, international cooperation, and public awareness.

My poster was selected for the special ACE gallery — displayed alongside work from larger youth organizations and country delegations. For me, it was a meaningful opportunity to represent our region on such a significant platform.

As for the role of NGOs in Bonn: I personally believe it was an important opportunity — one that, for various reasons, we still struggle to fully seize. Visa issues and lack of funding for advocacy activities remain serious barriers for EECCA region representatives to participate in international climate negotiations.

That said, the Bonn sessions tend to be smaller in scale, making it easier to connect with decision-makers — if your organization is prepared to push its agenda.

Anisa Abibulloyeva, Little Earth, Tajikistan

Anisa Abibulloyeva, Little Earth, Tajikistan

This was my first time attending the Bonn negotiations, and what stood out to me most was how much more open and accessible the process is for observers compared to COP. My main focus was on the sessions under the Action for Climate Empowerment (ACE) track. I tried to raise issues relevant to our region, especially around how to build effective advocacy strategies in countries where civil society is under constant pressure. Platforms like these are crucial for sharing experiences and developing approaches that take into account complex political and social contexts.

Access to these spaces remains a challenge — even at the level of accreditation. Although I had funding to attend, getting a badge was difficult. Even large organizations like Women Engage for a Common Future (WECF), who supported my participation, were unable to provide accreditation. It was only thanks to the solidarity of our regional network — in particular, colleagues from the Armenian organization Khazer — that I was ultimately accredited. Gaining access to these negotiations is, in itself, a matter of climate justice.

I also joined the Women and Gender Constituency, where, unfortunately, there are still almost no participants from Central Asia. I was the only representative from our region. Through the support of WECF and the Dutch network WO=MEN, I had the opportunity to join a meeting with the Dutch delegation, where I shared Little Earth’s experience working on a just energy transition in the mountain areas of Tajikistan. The discussion was meaningful, and the Dutch delegation expressed solidarity with civil society in the EECCA region. Meetings like this help delegates better understand real conditions on the ground and reflect those in the negotiations.

The SB sessions in Bonn offer more opportunities for engagement — especially compared to COP. Here, civil society actually has the chance to attend working meetings, speak with delegations, and contribute to the process. However, the weak representation of our region was noticeable. Delegations were small, and the voice of civil society was barely heard. We are still far behind regions like Latin America or Africa in terms of presence and influence. Even though COP29 took place in our broader region, Central Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Caucasus still remain on the margins of global attention. Civil society does not have equal access everywhere — and if we want a just transition, the international climate community must be willing to hear and include everyone, not just those with the most resources and the loudest voices.

Still, I was glad to see Kyrgyzstan’s delegation promoting a mountain agenda and Kazakhstan’s activity within the Baku Water Dialogue. But overall, the sense of fragmentation remains — our regional agenda is rarely heard, and our shared challenges remain largely invisible to the international community.

We still have a long way to go to be truly heard. Our region needs stronger coordination, institutional support, and international backing. It’s essential to host side events for broader international audiences, share our experiences, and actively take part in dialogues and decision-making processes. That’s how we can ensure our region’s voice becomes visible — and truly influences the global climate agenda.

Vladimir Slivyak – EcoDefense! environmental group

Vladimir Slivyak – EcoDefense! environmental group

In Bonn, we held a joint presentation with IPPNW on a report about African countries’ plans to develop nuclear energy. This report was published just before the Bonn negotiation session by 10 organizations from Africa and Europe.

The topic of nuclear energy is becoming increasingly important for two reasons.

The first reason: this technology is not suitable for addressing climate change — it is too dangerous, too expensive, and highly inefficient. It delivers emissions reductions too slowly, and even then, the results are minimal. Investing in nuclear energy diverts much-needed funding from more effective and proven renewable energy solutions.

The second reason: the nuclear industry is actively trying to gain access to funding that is meant for climate action. Environmental organizations believe that developing nuclear energy as a climate solution is counterproductive and dangerous.

In recent years, we’ve seen a surge in pro-nuclear propaganda targeting developing countries, including many in Africa. The goal is to convince governments to invest in new nuclear power plants. If this happens, the climate benefits will be negligible, but the risks for people and the environment will multiply. From the perspective of environmental organizations, including CAN, climate finance should go toward renewable energy — a safer, more effective, and increasingly affordable alternative.

The expansion of nuclear energy is a false solution. It’s essential that policymakers and civil society around the world understand this. Unfortunately, nuclear propaganda was also present at the Bonn session. That’s a troubling sign. In my opinion, the UNFCCC Secretariat should take measures to limit the promotion of false climate solutions. Yet we continue to see lobbyists from both the nuclear and fossil fuel industries feeling quite comfortable at the negotiations, with extensive access to promote their agendas.

The reflections from participants confirm: the voice of Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia is still too quiet in global climate negotiations. But every step, every statement, every poster — is a contribution toward making our region visible on the global climate map.

Ahead lies COP30 in Belém, Brazil. That’s where decisions will be made — decisions that will shape how resources are allocated, how vulnerability is recognized, and how responsibility is shared. Whether EECCA countries are visible in that process depends largely on the groundwork laid in Bonn.